The GISt of Missing Bobwhites

Every May for the past 3 years, our research team has spent one morning a week at our Lewis Township facility in Brown County, listening for the mating calls of bobwhite quail. Starting before dawn, the team listens intently for their calls, hoping to hear at least one as a sign of their return to the area. Bobwhites have become a rarity in these parts and their natural habitats have experienced severe decline as small farms intermixed with forests and hedgerows are replaced by large row-crop fields. Our hope has been that as we transition this farm back to one with more bobwhite friendly elements, we will see their return. Unfortunately the team failed to hear any bobwhites, the same outcome as years 1 and 2. To get a better sense of why we weren’t seeing a reversal in this trend, Research Intern Luke Weyer chose to perform a habitat suitability assessment of the Lewis Township facility as his summer intern project.

A habitat suitability model measures the quality of habitat based on three life requisites: winter food, cover, and nesting. In order for bobwhites to thrive, all three must be provided by the environment.

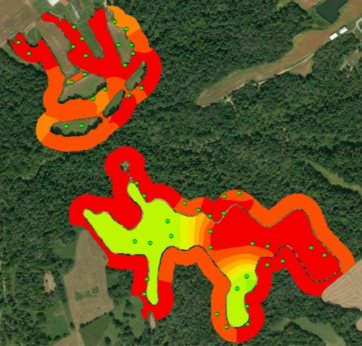

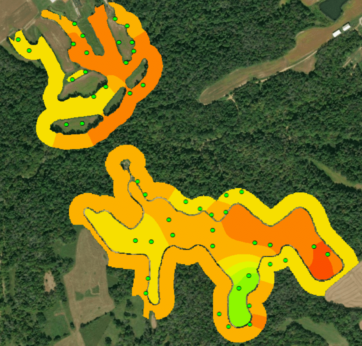

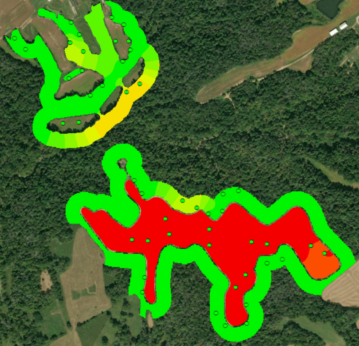

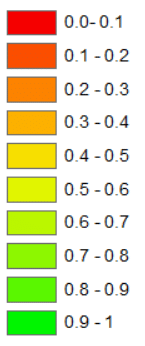

“The data I collected on these variables were integrated into a geographic information system (GIS) to generate suitability maps for each requisite (see image). The results were less than stellar and not unexpected, given the lack of bobwhite calls. The model found moderate, but also adequate, suitability for both cover and nesting, yet food was much lower making it the limiting factor.”

– Luke Weyer, Research Intern

With this new data in hand, we have hope for future years. The native warm season grasses planted at Lewis Township are establishing well which will provide excellent habitat for bobwhites. These grasses provide the bobwhite more opportunities to find sheltered food sources, as well as more nesting cover. “After the completion of my project, a bobwhite was heard near the property in August, so I think we’re moving in the right direction with our efforts” continues Weyer, “I look forward to what the future holds”.

Greenacres plans to continue monitoring and improving habitats for bobwhites in Brown County.