Mandala Art

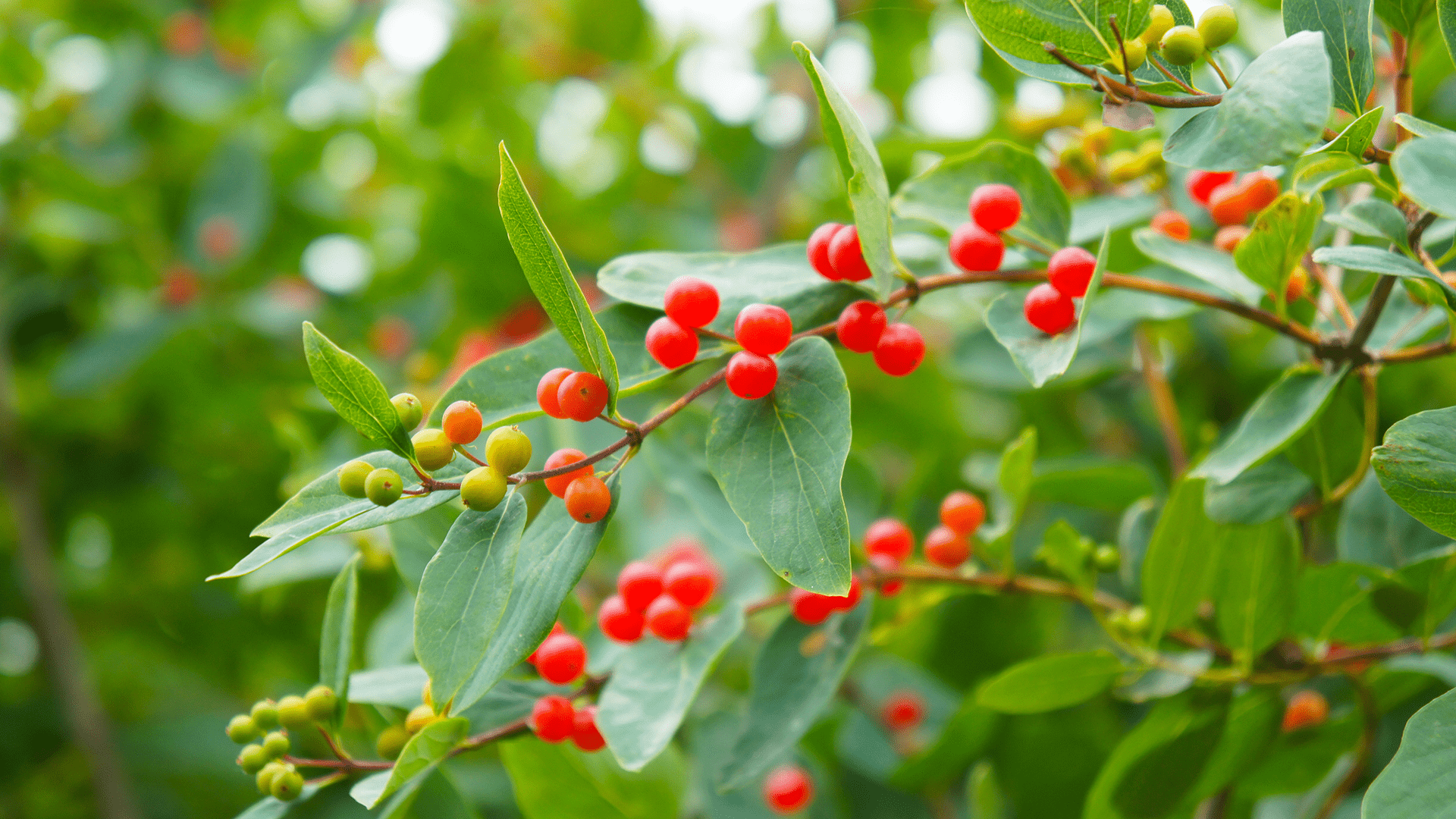

Out walking my dog on a lovely spring day, everywhere I look, every blossoming tree, dandelion, every pine cone and sweet gum seed- I see a small mandala. They have radial symmetry! Their design starts in the center and radiates out like the spokes of a bicycle wheel around the central hub. Amazing how all of these living things imitate art! Or should I say, art imitates life?

Download this coloring sheet to follow along with the video or get step-by-step instructions on how to draw your own.

The mandala is an ancient art form. The word mandala is from Sanskrit and literally means circle. Mandalas are circular designs filled with geometric or organic patterns with a radial symmetry. They can be simple or complex. They are used in architecture as exemplified in several features found at the Greenacres Arts Center. For example, the decorative wrought iron window grille works added in the 1930’s. The ironworks radiate from the central design which are children’s nursery rhyme characters. More symmetry can be found at the central entry courtyard’s garden. Original plans from A.D. Taylor shows beds of annuals in a modified plaid fabric design, which includes a grouping of 4-block patterns with walking paths in between thereby creating horizontal and vertical pattern of a plaid (see an example below).

The first mandala carved into stone dates back to the 1st century BCE. Mandalas are found in many cultures and religions around the world. One of the most recent archaeological finds happened in 2013 when someone reported seeing a giant mandala while using Google Earth! How exciting to discover that this ancient eight petal flower shape (Bihu Loukon), discovered in Manipur, northeastern India was one of the world’s largest mandalas made entirely of mud in a paddy field. The ancient star shaped structure could only be visible via Google Earth satellite imagery because of its huge size. The walls of the triangular arms of the star are approximately 15 feet thick and 5 feet high, with length of about 156 feet. Wow! Now that’s what I call a successful mandala hunt!

Just going outside for a walk is a way to relax, but incorporating that with a purpose: to search for radial designs in nature, made my walk so much more fun. You can even extend your search of radial symmetry to architecture that you pass. My dog may not have appreciated the slowed pace as much as I did, but now I see them everywhere I look! The mandala has been used for centuries as a way to meditate, relax and relieve stress. If you’d like to learn more about mandalas, see some examples from around the Arts Center here at Greenacres, or even learn how to draw your own, watch this video.

–Sandy Harsch