Late fall, after the first frost, is a good time for a foliar spray.

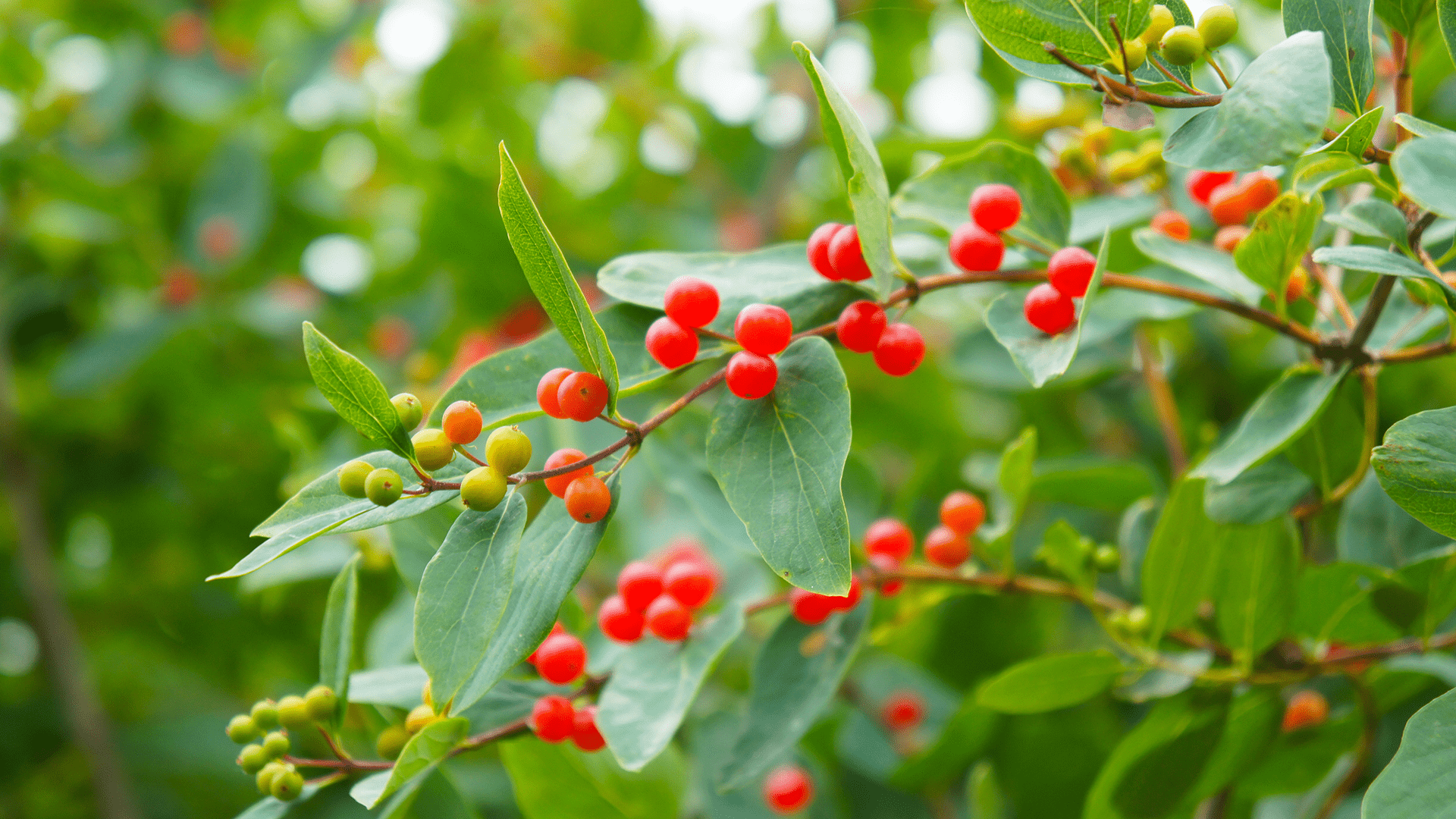

Honeysuckle stays green longer than most plants in our area and treating these shrubs now can lessen the impact on native species which have gone dormant. Before spraying the leaves of honeysuckle, make sure that the leaves are not falling off of the plant (gently tug a leaf and make sure it stays on the tree). If the leaves are already abscising, spraying them will not work to kill the honeysuckle.

Purchase a glyphosate solution. Dilute your glyphosate to about 1.25%. If your glyphosate is already diluted to around 40%, as many readily available brands are, this is somewhere between a 1:50 or 2:50 ratio of glyphosate solution to water. This can be mixed directly in a large plastic spray bottle. For large areas of coverage a backpack sprayer or hose attached to a tank may be more efficient.

Try to cover as much of the honeysuckle’s leaf area as possible. Take care to avoid spraying any native plants in the process. This method should eliminate about 90% of your honeysuckle; however, it is likely that follow up spot sprayings will need to occur the following fall due to plants that were missed, resilient, or emerged from seed.

Questions? Contact our Research Director, Chad Bitler at 513-898-3159